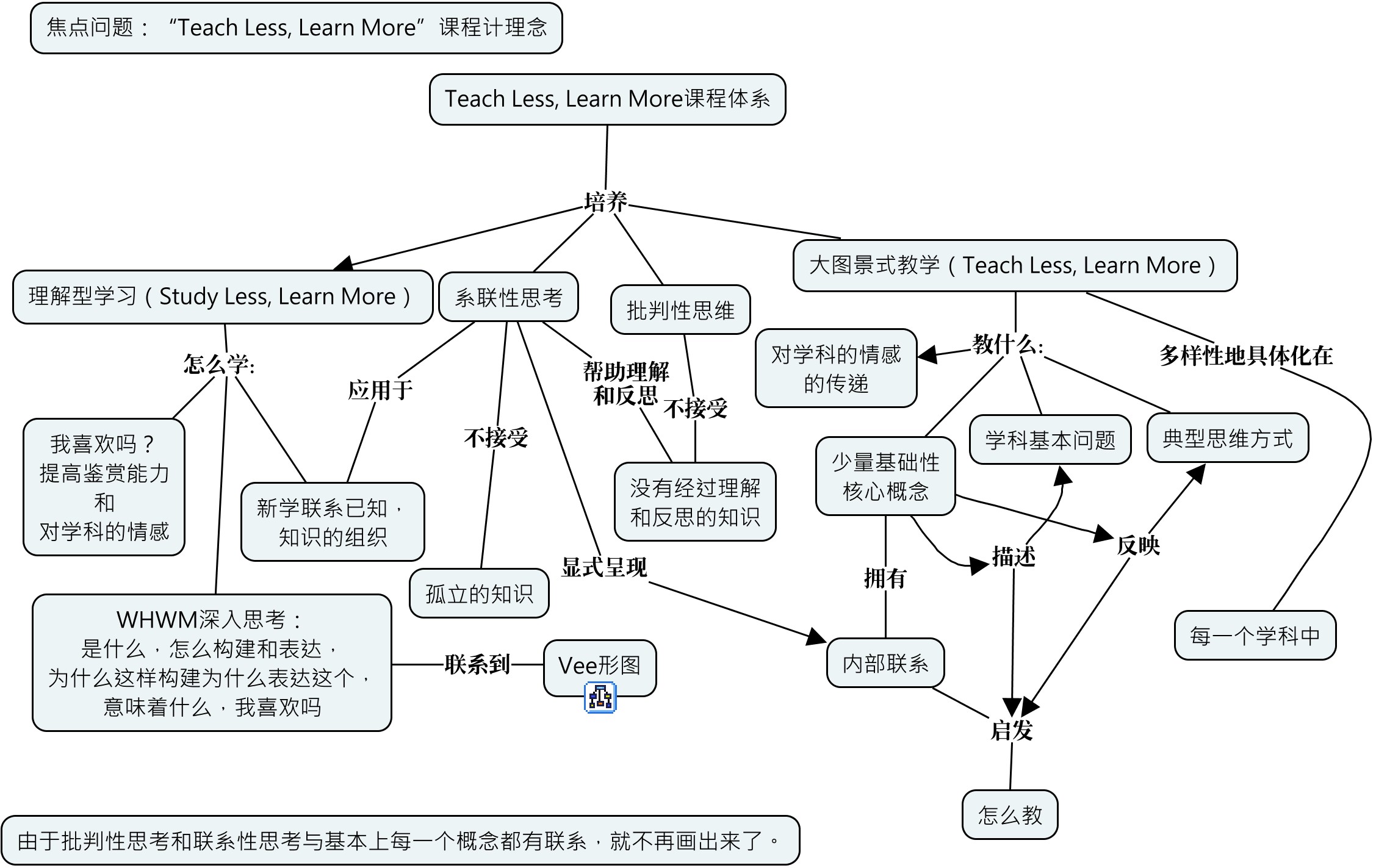

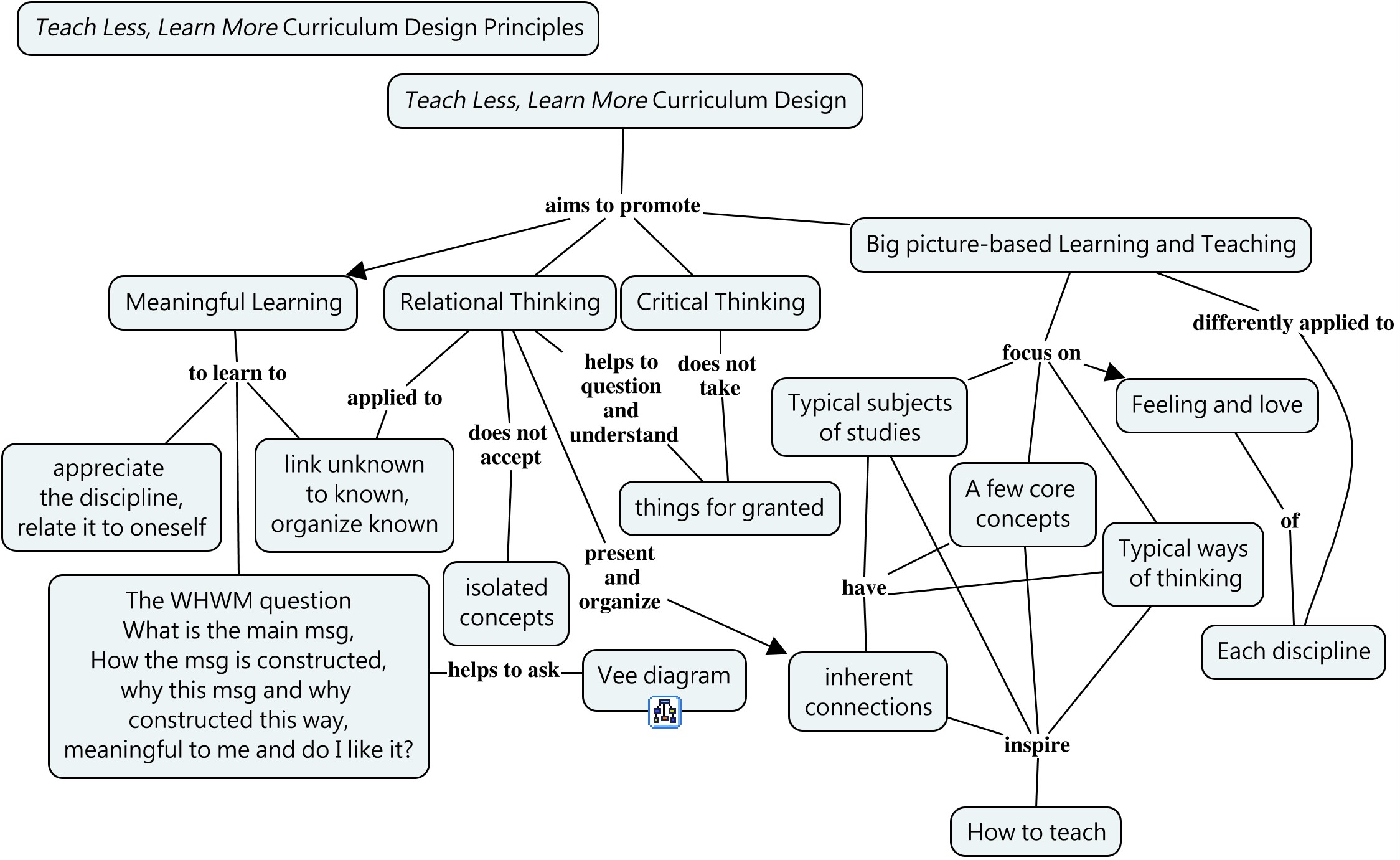

按照Teach Less, Learn More课程体系的一般设计要求和《学会学习和思考》的设计原则,我们做了《学会学习和思考科学和科学教育模块》的设计。

Meaningful Learning in a Systems Approach to Environmental Science: An Illustration of Learning How to Learn the Tools of Thinking

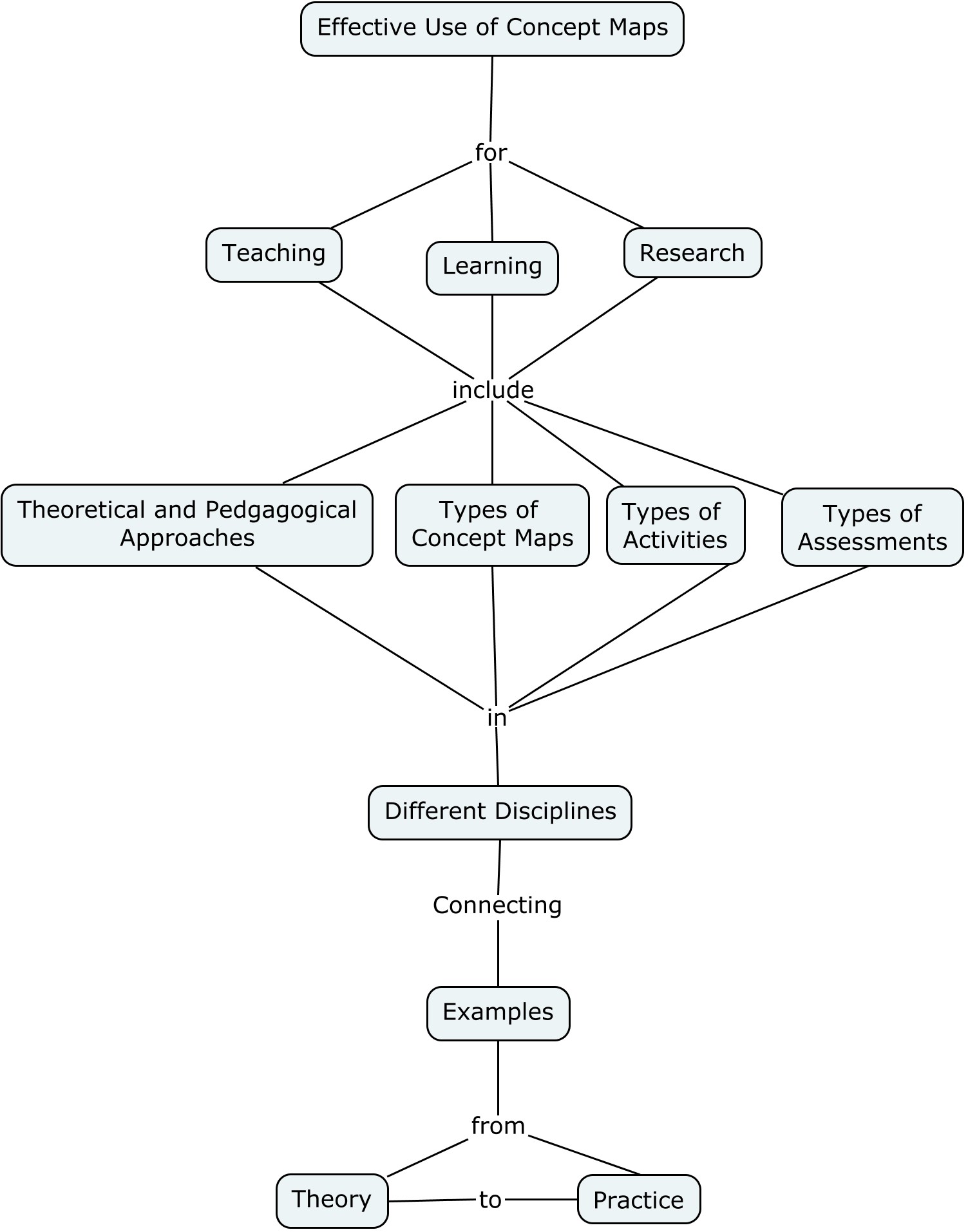

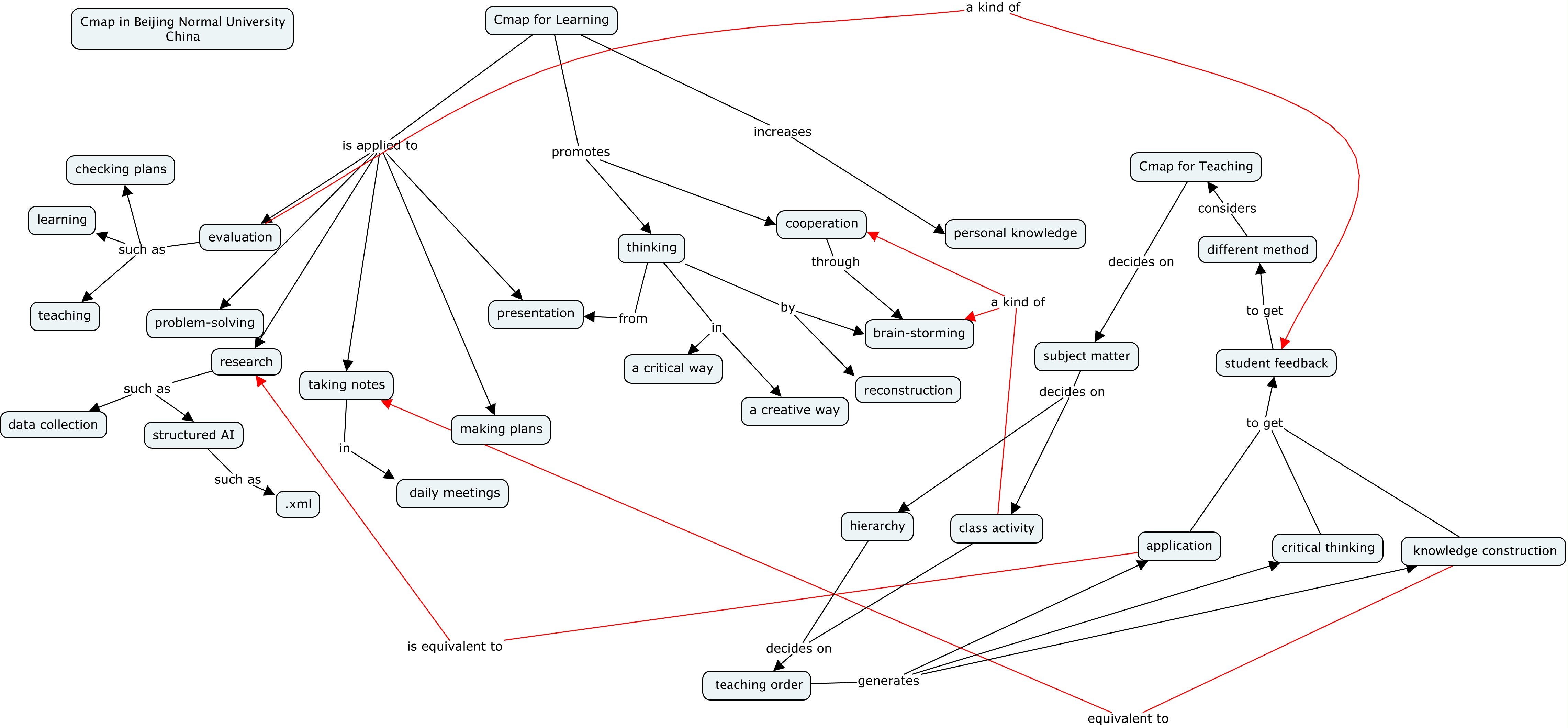

Concept Mapping and Vee Diagrams

Beijing Normal University, Oct. 10 – Oct. 21, 2016

Michael Brody PhD

Montana State University, College of Education, Health and Human Development

Bozeman, Montana USA

In this course students will use two meaningful teaching and learning techniques, concept mapping and Vee diagrams, to better understand a systems science approach in environmental science. Concept maps and Vee diagrams are explained in the book Learning How to Learn by Joseph Novak and D. Bob Gowin. (1984) We will use a website called the Habitable Planet: A Systems Approach to Environmental Science as the science content. This website was awarded the Science Prize for Online Science Resource in Education (SPORE) by the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). Each day the class will take a single chapter of the Habitable Planet and use concept mapping and Vee diagrams to analyze the content from a systems science approach. We will use Cmap software to build concept maps.

Meaningful Learning and Learning How to Learn: Concept Mapping and Vee Diagrams

Meaningful learning requires making connections among concepts and from concepts to experiences. When structured around core concepts, these connections lead to disciplinary expertise and insight.

Habits of mind characteristic of different disciplines develop in response to distinct challenges. As a result the structures of knowledge differ from one field to another. Concept mapping and Vee diagramming promise to bring such structures into focus, making learning efficient. (Concept maps are drawings that depict networks of relationships and hierarchy among concepts. Vee diagrams help the learner to represent the structure of knowledge in the context of a scientific inquiry.)

Habitable Planet: A Systems Approach to Environmental Science

https://www.learner.org/courses/envsci/

Earth is probably unique in the solar system, if not in the universe, because it is a platform that can support complex life forms. Conditions on Earth (temperatures, atmosphere, availability of minerals essential to life) are all maintained by a series of global cycles that link geological systems (plate tectonics, weathering, ocean, and atmospheric transport) with the diverse forms of life (particularly bacteria) that are present in almost every available niche.

The course begins by asking “What makes Earth unique among planets?” We will then go on to answer that question through the first four units, which provide a background for understanding and discussing the natural functioning of the different Earth systems: geophysical systems, the atmosphere, the oceans, and, finally, natural ecosystems. The next two units (“Human Population Dynamics” and “Risk, Exposure, and Health”) introduce humans as part of the overall ecosystem and look at what is needed to sustain human life. These are followed by a series of units that each deal with the effects of human actions on different natural systems: land use, air and water pollution, biodiversity decline, the extraction of resources, and finally, global issues such as climate change. The final unit looks toward the future and discusses in scientific terms what can be predicted, given current trends, as well as what might be expected if humans act in concert to mitigate their impact on the planetary system.

Accompanying each unit are video case studies that describe current, on-going research programs. Together, these case studies represent a fair cross section of the current “state of the art” in environmental science research. Designed to provoke curiosity and give a human face to many of the issues raised in the units, these videos will motivate and stimulate students to explore the themes through further readings and discussion.

Five interactive web simulations also reinforce the concepts we introduce, as well as teach about modeling environmental systems by providing opportunities to manipulate and experiment with natural systems.

Systems Thinking

The list of systems thinking skills is extensive and diverse, but mostly comprises the ability to see circular cause effect relations and the ability to synthesize elements to reveal a system’s structure. Specific systems thinking skills include: the ability to understand how the behavior of a system arises from the interaction of its agents over time (i.e. dynamic complexity); discover and represent feedback processes (both positive and negative) hypothesized to underlie observed patterns of system behavior; identify stock and flow relationships; recognize delays and understand their impact; identify nonlinearities; recognize and challenge the boundaries of mental (and formal) models. A number of evaluative testing studies have attempted to link systems thinking/system dynamics education with important skills such as efficient communication, planning, problem solving, and organizational development skills. (Molina and Medina-Borja 2006)

Expected Course Outcomes

Students will have a better understanding of:

- Concepts

- Learning how to learn and meaningful learning

- a systems approach to environmental science content

- how scientists conduct field and laboratory investigations in environmental science

- attitudes, values and beliefs related to environmental science content

- Skills

- how to use concept mapping to organize content and think deeper and clearly about environmental science

- learning by doing; discussion and critical feedback

- develop relational and critical thinking skills

- how to use the Vee diagram to analyze scientific investigations in environmental science

- how concept maps and Vee diagrams promote meaningful learning

- teaching concept mapping and Vee diagraming to your students

- Dispositions

- the value of concept mapping in learning how to learn

- the value of Vee diagrams in learning how to learn

- the value of a systems approach to environmental science

- importance of meaningful learning in environmental science

- value of higher order learning (application, analysis, synthesis, evaluation) in learning environmental science systems approach

- value of concept mapping and Vee diagrams in teaching for meaningful learning

Course Structure

- Students are expected to decide environmental science topics of their own choice and work in small groups

- Each class will focus on a section of the Habitable Planet; concept mapping the text and Vee diagraming the Scientific Investigations of each video

- There will be some small leactures but most of the class time will be about doing concept mapping of the environmental science content and Vee diagraming the research associated with each topic.

- Students in this class will prepare a concept map of a selected environmental science topic and present the map to the class

- Students will construct a Vee diagram of a unique research project related to the environmental science topic in their concept map

- The grade for the course is based on module reflections including both modules (50%), the final concept map of your unique environmental science topic (25%) and unique Vee diagram (25%)